Forest rights and heritage conservation (GS Paper 3, Environment)

Context:

- Of the 39 areas declared by UNESCO in 2012 as being critical for biodiversity in the Western Ghats, 10 are in Karnataka.

- Before recognising areas as world heritage sites, UNESCO seeks the opinion of the inhabitants on the implication of the possible declaration on their lives and livelihoods.

Case in Karnataka:

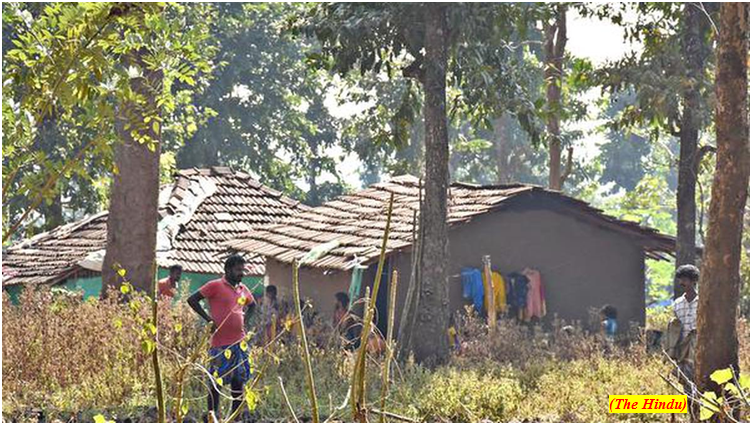

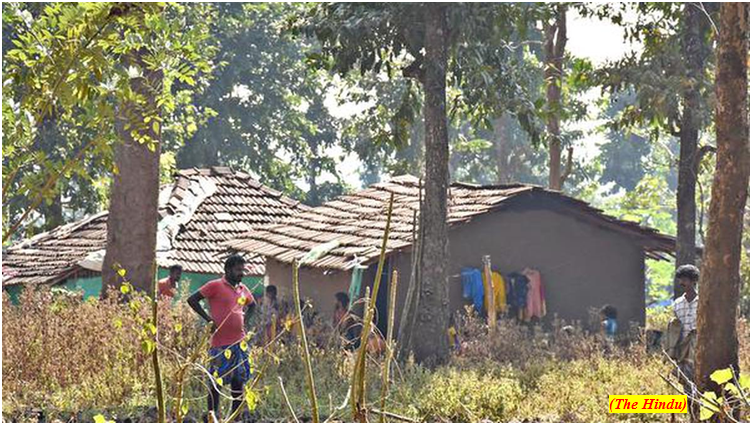

- The primary stakeholders in the gram panchayats located close to the world heritage sites in Karnataka were Scheduled Tribes (STs). Other traditional forest dwellers include Scheduled Castes (SCs), Other Backward Classes, minorities and the general category.

- An overwhelming majority said that they were not aware of the process that leads to the declaration of UNESCO heritage sites.

Forest Rights Act:

- The majority of the forest dwellers claimed land measuring not more than one acre. It is clear that the claims were nowhere close to the ceiling of four hectares permitted under the Forest Rights Act (FRA). The rejection rate of the other traditional forest dwellers was two times more than the STs.

- In the case of the STs, the reasons were attributed to fresh encroachments; the claimants not living on the lands claimed; claimed lands being on ‘paisari bhoomis’ (wasteland and forest lands which have not been notified as protected forests or reserved forests) or revenue lands; and multiple applications made in a single family.

- In the case of other traditional forest dwellers, it was mainly failure to produce evidence of dependency and dwelling on forest land for 75 years.

Restrictions in protected areas:

- The FRA is good law which recognises the rights of the STs because of their overall backwardness. However, most felt there should be a closure to this Act; and that the process cannot go on forever with new claims emerging on a regular basis.

- Presenting the declaration of the world heritage site in a positive light, they said that illegal tree-felling and poaching have come down following the stringent implementation of rules in the ‘protected areas’. Most forest dwellers acknowledged this fact.

- The people in the villages falling under eco-sensitive zones said they had started experiencing severe restrictions on their entry into the forest. Development activities like road repair has been stopped.

- Farming is not allowed in a normal way, a slight sound is demurred, the use of fertilizers is banned, and even a small knife is not allowed to be carried into the forest. The people are prohibited from cutting trees falling on their houses to undertake repair work or move the earth.

- A striking revelation was that these restrictions were in enforcement from the time these areas were declared as protected areas and not necessarily after their declaration as world heritage sites.

Concerns:

- The increasing animal insurgency is causing damage to the crops of the farming forest dwellers. Those who don’t have recognition over their lands are not given compensation for the loss.

- Monkeys and snakes released from urban settings into the forests enter their houses. More importantly, the monkeys do not survive in the wild for long.

- Owning livestock in the villages close to forests is more challenging than in regular revenue villages.

- In the areas where irrigation projects have come up, the affected people reported that grazing lands have been taken over by the government to compensate for the forest land lost to such projects.

Current status:

- In many places, people were accepting the resettlement packages and moving out of ‘protected areas’ for good. They worried that if half the village population moved away, it would become difficult for the remaining ones to live their normal life.

- Most forest dwellers said they were still deprived of basic facilities and other government benefits extended under various schemes and programmes as they don’t possess the ‘Records of Rights, Tenancy and Crops’ that is required along with the title of the land.

Need for government’s intervention in consonance with the rules of the Act:

- Half the world heritage sites in Karnataka fall under protected areas (National Park: 1; Wildlife Sanctuaries: 4) and the remaining are reserved forests. The issue becomes complicated when the people refuse to ‘re-locate’ on grounds of their attachment to the land fearing extinction of their culture and religious roots.

- The gram sabha appears supreme in the Act in deciding the ‘proposed resettlement’ as it has to give ‘free informed consent’. However, this does not happen.

- Hence, the government must bring more clarity to the Act to avoid conflicts between the government agencies conserving biodiversity and the people living in the forest for over decades and centuries.

Conclusion & Way Forward:

- Finally, the conservation of biodiversity requires special attention. Yet, forest dwellers willing to live in the forest must be allowed to stay. Many of them comply with the norms of the eco-sensitive zone because they do not depend on modern development needs such as the use of fertilizers and mobile phones.

- In the same breath, those wanting to experience the fruits of development must be relocated according to their choice of a new place and a suitable package.

- This can be possible only when the areas declared as ‘protected’ are arrived at after consultations with the local population. This did not take place in a transparent way at the time of the declaration of world heritage site or earlier, when protected areas were notified.