Are legislators immune to bribery charges? (GS Paper 2, Polity and Constitution)

Why in news?

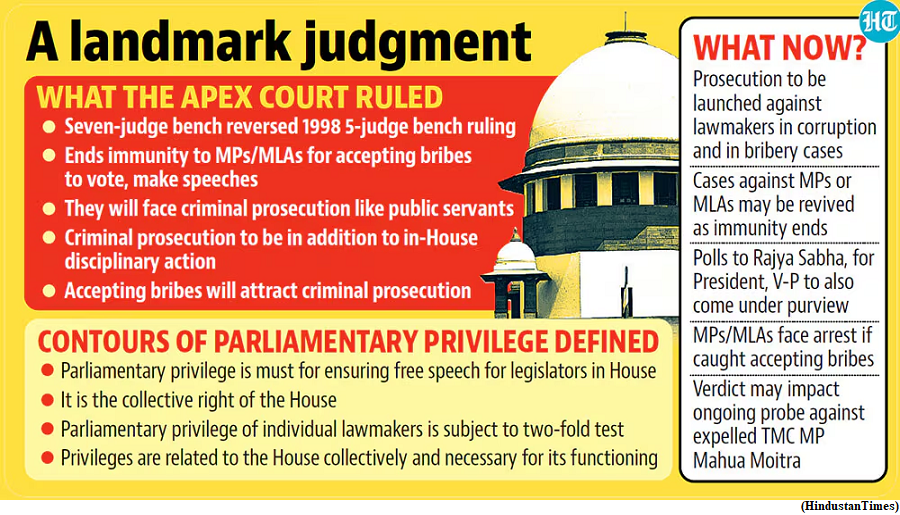

- A seven-judge Bench of the Supreme Court recently ruled that Members of Parliament (MPs) and Members of Legislative Assemblies (MLAs) cannot claim immunity from prosecution for accepting bribes to cast a vote or make a speech in the House in a particular fashion.

Details:

- Article 105(2) of the Indian Constitution confers on MPs immunity from prosecution in respect of anything said or any vote given in Parliament or on any parliamentary committee.

- Similarly, Article 194(2) grants protection to MLAs.

- A seven-judge Constitution Bench headed by Chief Justice of India (CJI) D.Y. Chandrachud unanimously overruled its 1998 judgment in P.V Narasimha Rao v. State and opened the doors for law enforcement agencies to initiate prosecution against legislators in bribery cases under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (Act).

What was the case?

- Sita Soren, a member of the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM), was accused of accepting a bribe to cast her vote in favour of a certain candidate in the Rajya Sabha elections of 2012. Soon a chargesheet was filed against her.

- In 2014, the Jharkhand High Court dismissed Ms. Soren’s plea wherein she claimed she enjoyed legal immunity under Article 194(2). The dismissal in the High Court led to an appeal being filed in the Supreme Court.

- On September 20, 2023, a five-judge Bench headed by CJI Chandrachud while hearing the appeal doubted the correctness of the majority view in P.V. Narasimha versus State (1998) and accordingly referred the matter to a seven-judge Bench while underscoring that it is an “important issue that concerns our polity”.

What was the 1998 ruling that was overruled?

- The P.V. Narasimha Rao ruling involves the 1993 JMM bribery case against former Union Minister Shibu Soren, the father-in-law of Sita Soren, the petitioner in the present case.

- Mr. Soren, along with some of his party members, were accused of taking bribes to vote against the no-confidence motion against the then P.V. Narasimha Rao government.

- While two judges on the Constitution Bench opined that legislative immunity granted under the Constitution could not be extended to such cases, the majority of them, while acknowledging the seriousness of the offence, ruled that "a narrow construction of the constitutional provisions" may result in the impairment of the guarantee of “parliamentary participation and debate”.

What did the top court rule now?

No violation of the doctrine of stare decisis

- During the proceedings, the petitioners raised a preliminary objection that overruling the long-settled law in P.V. Narasimha Rao is impermissible owing to the doctrine of stare decisis a legal principle that obligates judges to adhere to prior verdicts while ruling on a similar case.

- However, such contention was dismissed by observing that the doctrine is not an “inflexible rule of law” and that a larger bench is well within its limits to reconsider a prior decision in appropriate cases.

Legislative privileges have to conform with constitutional parameters

- Tracing the history of parliamentary privileges in India, the Court said that unlike the House of Commons in the United Kingdom, India does not have ‘ancient and undoubted’ rights vested after a struggle between the Parliament and the King.

- Instead, such rights in India have always flown from a statute, which after independence transitioned to a constitutional privilege. Thus, whether a claim to privilege in a particular case conforms to the parameters of the Constitution is amenable to judicial review.

Constitutional immunity from bribery charges does not fulfill “two-fold test”

- While elaborating upon the purpose of Articles 105 and 194, the Chief Justice pointed out that such privileges are guaranteed to sustain an environment in which debate and deliberation can take place within the legislature.

- However, such a purpose is destroyed when a member is induced to vote or speak in a certain manner following an act of bribery.

- He also highlighted that the assertion of any such privilege will be governed by a two-fold test:

- The privilege claimed has to be tethered to the collective functioning of the House and

- Its necessity must bear a functional relationship to the discharge of the essential duties of a legislator.

Bribery not immune just because it is not essential to the way a vote is cast

- Clause (2) of Article 105 has two limbs. The first prescribes that a member of Parliament shall not be liable before any court in respect of “anything said or any vote given” by them in Parliament or any committee thereof. The second limb prescribes that no person shall be liable before any court “in respect of” the publication by or under the authority of either House of Parliament of any report, paper, vote or proceedings.

- In P.V. Narasimha Rao, the Court observed that the expression “in respect of” in Article 105(2) must receive a “broad meaning” to protect MPs from any proceedings in a court of law that relate to, concern or have a connection or nexus with anything said or a vote given by him in the Parliament. It therefore concluded that a bribe given to purchase the vote of an MP was immune from prosecution under this provision.

- However, the Chief Justice reasoned that the expressions “anything” and “any” must be read in the context of the accompanying expressions in Articles 105(2) and 194(2). Thus, the words “in respect of” means ‘arising out of’ or ‘bearing a clear relation to’ and cannot be interpreted to mean anything which may have even a remote connection with the speech or vote given.

Offence of bribery complete the moment illegal gratification is taken

- Bribery is not rendered immune under Article 105(2) and the corresponding provision of Article 194 because a member engaging in bribery commits a crime which is not essential to the casting of the vote or the ability to decide on how the vote should be cast. The same principle applies to bribery in connection with a speech in the House or a Committee, the court elucidated.

- Section 7 of the Prevention of Corruption Act strengthens such an interpretation since it expressly states that the “obtaining, accepting, or attempting” to obtain an undue advantage shall itself constitute an offence even if the performance of a public duty by a public servant has not been improper.

Courts and the House can exercise parallel jurisdictions

- The petitioners argued that the exercise of the Court’s jurisdiction is unwarranted since corruption charges against a parliamentarian are treated as a breach of privilege by the House resulting in expulsion or punishment.

- Dismissing such an argument, the verdict pointed out that the Court’s jurisdiction to prosecute a criminal offence and the authority of the House to take action for a breach of discipline operate in distinct spheres.

- Thus, judicial proceedings cannot be excluded merely because bribery charges can also be treated by the House as contempt or a breach of its privilege.

Legislative privileges apply equally to Rajya Sabha elections

- The Court also clarified that the principles enunciated by the verdict regarding legislative privileges will apply equally to elections to the Rajya Sabha and to appoint the President and Vice-President of the country. Accordingly, it overruled the observations in Kuldip Nayar v. Union of India (2006), which held that elections to the Rajya Sabha are not proceedings of the legislature but a mere exercise of franchise and therefore fall outside the ambit of parliamentary privileges under Article 194.

- It also pointed out that immunity guaranteed to legislators has been colloquially called a “parliamentary privilege” and not “legislative privilege” for a reason.

- Thus, it cannot be restricted to only law-making on the floor of the House but extends to other powers and responsibilities of elected members, which take place in the legislature or Parliament, and even when the House is not in session.

- Additionally, the petitioners argued that the exercise of the Court’s jurisdiction is unwarranted since the Parliament also has the power to punish its members for contempt either by suspending them or sentencing them to a jail term.

- Dismissing this, the Court said that parallel jurisdictions can be exercised since its jurisdiction to prosecute a criminal offence and the authority of the House to take action for a breach of discipline operate in distinct spheres.