Fewer cyclones in Bay of Bengal but frequency increased in Arabian Sea: Report (GS Paper 1, Geography)

Why in news?

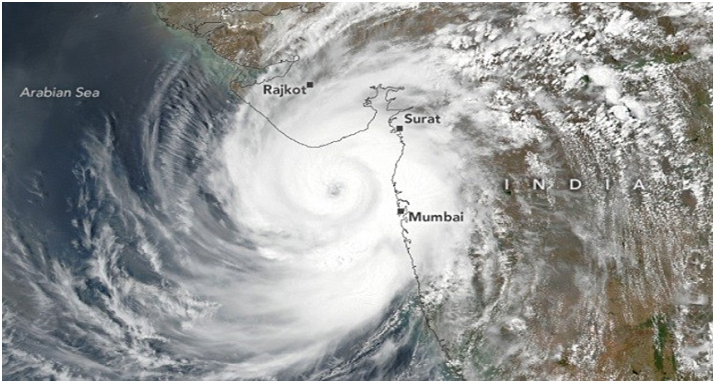

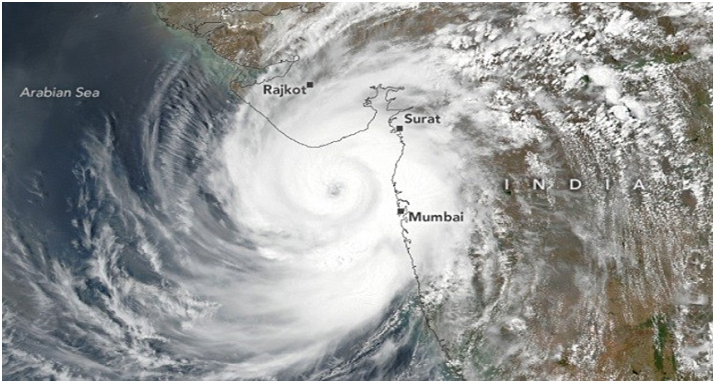

- Northern Indian Ocean cyclones may have gained notoriety for causing considerable devastations, but a new research has noted a decline in the Bay of Bengal.

- The Arabian Sea, however, has registered an increase in the last two decades, according to researchers from the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) in Bhopal. They attributed this trend to global warming.

Vertical shear:

- With the greenhouse gases increasing and the earth warming, not only does temperature and humidity increase but also winds change and become weaker simultaneously.

- One thing in the atmosphere that inhibits the growth of cyclones is called the vertical shear, which refers to how strongly the winds can change from the surface to the top of the atmosphere, for up to 10 kilometres or so.

- The strong vertical shears suppress cyclones, the expert added. “Weak vertical shears increase cyclones. While the global trend reflects a decrease in cyclones, there has been an increase in cyclones over certain parts of the world, including the Northern Indian Ocean (Arabian Sea).

Key Findings:

- The India Meteorological Data (IMD)’s data for the 130-year-long study period found an average of 50.5 tropical cyclones per decade over the region comprising the Bay of Bengal in the East and the Arabian Sea in the West.

- The researchers found that 49.8 per cent of tropical cyclones occurred from October-December in the post-monsoon period, while 28.9 per cent of the cyclones occurred in the pre-monsoon season between April to June during the same 130-year period.

- Overall, 80 per cent of the tropical cyclones occurred in the pre- and post-monsoon months.

Increase in cyclones over the Arabian Sea:

- The Arabian Sea side of the north Indian Ocean, however, saw a 52 per cent increase in cyclonic storms (63-88 km per hour) from 2001 -2019.

- The frequency increase in very severe cyclonic storms, extremely severe cyclonic storms and super cyclonic storms in the Arabian Sea was observed during the post-monsoon months. As an exception, 2019 witnessed five tropical storms over the Arabian Sea and three over the Bay of Bengal.

- In comparison to the Bay of Bengal, the proportion of Arabian sea cyclones was initially 1:4, but in current study, found that it has become 2:4 from 2001-2020.

Sea surface temperature:

- They studied the characteristics of the Arabian Sea cyclones using three wind-energy drive metrics, namely power dissipation index (PDI), accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) and accumulated cyclone intensity (ACI), which demonstrated that the length, energy and intensity of these cyclones increased over the last 20 years.

- In contrast, the frequency of Bay of Bengal cyclonic storms has slightly decreased but not to a significant extent. The reason is that there is a warming threshold for sea surface temperature (SST) over any ocean. It is generally between 26 degrees Celsius and 30 degrees Celsius, which has already been achieved in the Bay of Bengal.

- However, sea surface temperature is still gradually increasing over the Arabian Sea. Some studies have reported a 0.5-0.7 degree Celsius increase of SST over the Indian Ocean, but more studies have tobe done for greater accuracy.

- The researchers examined the Bay of Bengal tropical cyclones from 1982-2020 and found that El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) years reported more tropical cyclonic activity over the region.

- They reported a shift in tropical cyclogenesis during the time, which refers to the various stages of its formation, in terms of sea surface temperature, humidity, force, disturbance and atmospheric instability.

WHO Global TB Report 2022

(GS Paper 2, Health)

Why in news?

- Recently, the WHO released the Global TB Report 2022.

- The Report notes the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis, treatment and burden of disease for TB all over the world.

Findings related to India:

- India’s TB incidence for the year 2021 is 210 per 100,000 population – compared to the baseline year of 2015 (incidence was 256 per lakh of population in India); there has been an 18% decline which is 7 percentage points better than the global average of 11%.

- These figures also place India at the 36th position in terms of incidence rates (from largest to smallest incidence numbers).

How India was able to successfully offset the disruptions caused by COVID-19 pandemic?

- While the COVID-19 pandemic impacted TB Programmes across the world, India was able to successfully offset the disruptions caused, through the introduction of critical interventions in 2020 and 2021,this led to the National TB Elimination Programmenotifying over 21.4 lakh TB cases, 18% higher than 2020.

- This success can be attributed to an array of forward-looking measures implemented by the Programme through the years, such as the mandatory notification policy to ensure all cases are reported to the government.

- Further, intensified door-to-door Active Case Finding drives to screen patients and ensure no household is missed, has been a pillar of the Programme. In 2021, over 22 crore people were screened for TB.

- The aim has been to find and detect more cases to arrest onwards transmission of the disease in the community which has contributed to the decline in incidence. For this purpose, India has also scaled up diagnostic capability to strengthen detection efforts.

- Indigenously-developed molecular diagnostics have helped expand the reach of diagnosis to every part of the country today. India has over 4,760 molecular diagnostic machines across the country, reaching every district.

National Prevalence Survey:

- Against this backdrop, and prior to the publication of the Global Report, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare had communicated to WHO that the Ministry has already initiated domestic studies to arrive at a more accurate estimate of incidence and mortality rates in a systematic manner and India’s data will be provided after conclusion of studies in early part of 2023.

- The WHO has also acknowledged the Health Ministry’s position on this and noted in the Report that “estimates of TB incidence and mortality in India for 2000–2021 are interim and subject to finalization, in consultation with India’s Ministry of Health & Family Welfare”.

- The results of the Health Ministry’s study, initiated by the Central TB Division (CTD), will be available in approximately six months’ time and shared further with WHO. These steps are in line with India conducting its own National Prevalence Survey to assess the true TB burden in the country – the world’s largest such survey ever conducted.

- The WHO Report notes that India is the only country to have completed such a survey in 2021, a year which saw “considerable recovery in India”.

Ni-kshayPoshanYojana:

- The WHO Report notes the crucial role of nutrition and under-nutrition as a contributory factor to the development of active TB disease.

- In this respect, the TB Programme’s nutrition support scheme, Ni-kshayPoshanYojana has proved critical for the vulnerable. During 2020 and 2021, India made cash transfers of 89 million dollars (INR 670 crores) to TB patients through a Direct Benefit Transfer programme.

- Moreover, in September 2022, the President of India has launched a first-of-its-kind initiative, Pradhan Mantri TB Mukt Bharat Abhiyan to provide additional nutritional support to those on TB treatment, through contributions from community including individuals and organizations.

Gilgit-Baltistans significance for India

(GS Paper 2, International Relation)

Why in news?

- Recently, the Defence Minister said that the government has started its development journey in the Union Territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh and its northward journey will be complete after reaching “the remaining parts (of Pakistan occupied Kashmir), Gilgit and Baltistan”.

- He said this would “implement the resolution passed unanimously by India’s Parliament” on 22 February 1994 while speaking at the ShauryaDiwas celebrations on the outskirts of Srinagar.

What is Gilgit-Baltistan?

- Parts of Kashmir have been illegally occupied by Pakistan since 1947.

- Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK) comprises two different regions, one which the neighbouring nation calls ‘Azad Jammu and Kashmir’ (AJK) and the other is Gilgit-Baltistan (GB).

- GB is the northernmost tip of Kashmir and covers part of Ladakh. It provides a land route with China, meeting Xinjiang Autonomous Region.

- To its south is the other part of PoK; to the east is Jammu and Kashmir and Afghanistan is to its west. The GB region makes up 86 per cent of PoK.

How did Pakistan occupy the region?

- Gilgit was part of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir and in 1935, Hari Singh, the ruler of the state, leased it to the British. After Independence, they decided to return Gilgit to the maharaja.

- On October 22, 1947, tribal militias backed by Pakistan poured into the valley and marched towards Srinagar, in accordance with Operation Gulmarg.

- Hari Singh, the Hindu-ruler of the princely state then sought assistance from India and signed the Instrument of Accessionon 26 October, making Jammu and Kashmir a part of India, following which the Indian Army landed in the valley to push back the Pakistani invaders.

- In Gilgit, meanwhile, a rebellion broke out against Hari Singh. On November 1, a local political outfit called Revolutionary Council of Gilgit-Baltistan proclaimed the independent state. In just a span of two weeks, the group announced its accession with Pakistan.

- After the British returned Gilgit to Hari Singh in 1947, the ruler sent his representative Brigadier Ghansar Singh, as Governor. However, Gilgit Scouts, who were led by British Major William Alexander Brown rebelled. The officer illegally offered the region to Pakistan, who occupied it on November 4, 1947.

- In 1949, Pakistan entered into an agreement with the 'provisional government' of Azad Jammu & Kashmir (AJK), to take over its affairs. Under that agreement, the AJK government also ceded the Gilgit-Baltistan administration to Pakistan.

- Pakistan named the region, GilgitWazarat and Gilgit Agency, as The Northern Areas of Pakistan and it is directly administered by the country’s government.

What do the people of G-B want?

- While the residents of the region expressed a desire to join Pakistan after gaining Independence, the neighbouring country did not merge the region, citing its territorial link to Jammu and Kashmir.

- The people of G-B have been demanding merger for years, so that they could enjoy the same Constitutional rights that Pakistanis have.

What is the 1994 resolution passed by India?

- The resolution on PoK underlined the Indian government’s consistent and principled position and was adopted unanimously by both Houses of Parliament on 22 February 1994.

- The resolution states that “the entire Union Territories of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh have been, are and shall be an integral part of India”. It demanded Pakistan vacate its illegally occupied territories in the region.

- On 4 April 2018, the United Kingdom Parliament said that Gilgit-Baltistan belongs to India as an integral part of Jammu and Kashmir after it legally acceded to the Union in 1947.

- The motion reads, “Gilgit-Baltistan is a legal and constitutional part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, India, which is illegally occupied by Pakistan since 1947, and where people are denied their fundamental rights including the right of freedom of expression.”

- In November 2019, when a new map of India showed the area as part of the newly created Union Territory of Ladakh, both Pakistan and China objected to it.

What’s the status of the region now?

- In 2009, Pakistan passed the Gilgit-Baltistan (Empowerment and Self-Governance) Order, granting the region a Legislative Assembly and chief minister. A governor would be appointed by the president. Until then the region was called Northern Areas and ruled by the executive.

- However, in 2018 then-Pakistan Muslim League (N) government passed an order to limit the powers of the Assembly. This was done so that it would have greater control of the region and other resources for the infrastructure projects being planned under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), according to a report in The Indian Express.

- In 2019, the Pakistan Supreme Court repealed the order, instructing the Imran Khan-led government to bring in governance reforms. However, this was not done. The top court appointed a caretaker government until the next Legislative Assembly elections.

- In November 2020, Imran Khan said that the region would be given a “provisional provincial status”. But this also has not happened yet.

Why is Gilgit-Baltistan important to India?

- India has always maintained that this region belongs to it. However, its strategic importance has only increased with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a collection of infrastructure projects in the Muslim-majority nation.

- As part of its Belt and Road Initiative, China has put a huge investment in the area. With tensions between India and China in Eastern Ladakh, India is worried about a two-front conflict.

- India has been emphasising taking control of the region. On 11 March 2020, the government said, “consistent and principled position, as also enunciated in the Parliament resolution adopted unanimously by both Houses on 22 February 1994, is that the entire Union Territories of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh have been, are and shall be an integral part of India”.

- It said that the government “monitors all developments taking place in the territories of India including in territories that are under the illegal and forcible occupation of Pakistan”.

The death penalty and humanising criminal justice

(GS Paper 2, Judiciary)

Context:

- As a conservative agency of the state, the Supreme Court of India is ordinarily expected to follow the path laid out in the Constitution and the binding precedents.

- But there do come some exceptional moments when, either because of inspired leadership or the burden of anomalous operations of criminal justice, the agencies feel free to break the chains that force it to the conservative frame.

Verdict on‘death-row prisoners’:

- It must go to the credit of the Chief Justice of India (CJI), Justice U.U. Lalit that as the 49th CJI of India, he has ushered in that rare moment by taking several bold initiatives to correct certain grave anomalies that have persisted in operation of the death penalty law.

- Even before taking up the office of the CJI, Justice Lalit had displayed unique sensitivity to the plight of the condemned ‘death-row prisoners’ in Anokhilal vs State of M.P. (2019), Irfan vs State of M.P., Manoj and Ors vs State of M.P. (May 2022), and impart corrections in the form of creative directions/guidelines.

On policies and uniformity:

- The focus here is on reframing ‘Framing Guidelines Regarding Potential Mitigating Circumstances to be Considered While Imposing Death Sentences’, a decision authored by the three judge Bench (the current CJI and Justices Ravindra Bhat and Sudhanshu Dhulia, September 19, 2022).

- The decision stands out because of the thrust on the trial court’s death sentencing policies and the practice and desire to elicit, from a larger Bench, directions to ensure some kind of uniformity in the matter.

- Such a reference to a larger Bench would constitute yet another step in the direction of death penalty sentencing justice reform such as the legislative limitation flowing from Section 354(3) in the Code of Criminal Procedure; judicial limitation flowing from the ‘rarest of rare’ case; and ‘oral hearing’ after all the remedies to the condemned are exhausted.

- The three judge Bench’s decision has summed up the core issue that displays a special concern for the legislative mandate under Section 235(2) conferring a right to pre-sentence hearing after conviction and its endorsement by the full Bench ruling in Bachan Singh; the trial courts and the appellate court’s display of a conflicting patterns of compliances.

Real and meaningful opportunity:

- With this foundational background and the context of the wide-spread discrepancies in the interpretation of the law, the following observations of the Court are significant:

- It is also a fact that in all cases where imposition of capital sentence is a choice of sentence, aggravating circumstances would always be on record, and would be part of prosecutor’s evidence, leading to conviction, whereas the accused can scarcely be expected to place mitigating circumstances on the record, for the reason that the stage for doing so is after conviction. This places the convict at a hopeless disadvantage, tilting the scales heavily against him.

- The three-judge Bench held that it is necessary to have clarity in the matter to ensure a uniform approach on the question of granting real and meaningful opportunity, as opposed to formal hearing to the accused/convict on the issue of sentence.

Positive response:

- The Constitution Bench may come up with new guidelines under which the trial courts themselves can hold a comprehensive investigation into factors related to upbringing, education and socio-economic conditions of an offender before deciding the punishment.

- The subjective factors identified in Manoj and Ors. vs State of M.P., said: “trial court must take into account the social milieu, the educational levels, whether the accused had faced trauma earlier in life, family circumstances, psychological evaluation of a convict and post-conviction conduct, were relevant factors at the time of considering whether the death penalty ought to be imposed upon the accused”.

Future roadmap:

- The appreciation generated by the bold initiative of the three judge Bench under the leadership of the CJI might have made a positive mark, but the future shape of the mission to humanise criminal justice will ultimately depend upon two things.

- The first is the composition of the larger Bench and the inclination of the judiciary to continue in its onward creative path, as the CJI retires.

- Second, the extent to which society is prepared to broaden the horizons of meaningful hearing, even to the earlier guilt determination stage.

- Hitherto, criminal liability is a product of the component of culpability/guilt and sanction/punishment. The consideration of these two components in isolation leads to a disconnect between the wrongdoer and his punishment or sentence.

Conclusion:

- Should the ‘mitigating factors’ influence only the sentence, and not alter the nature and quality of the guilty mind, or the ‘guilt’ that constitutes the stock justification for punishment?

- How long and at what cost should we continue to ignore the ‘quality’ of the guilty mind of the ‘death row prisoners’ who suffer from severe to mild psychiatric disorders before and after crime (according to empirical evidence in chapter IV of the Deathworthy report?

- Perhaps, there will be some answers from leads given by western critical criminal law scholars who have already begun making a distinction between ‘early guilt’ that is regressive, prosecutory and punitive, and ‘mature guilt’ that is developmental and progressive.