The untapped potential of stem cells in menstrual blood (GS Paper 3, Science and Technology)

Context:

- Although scientists had isolated adult stem cells from many other regenerating tissues including bone marrow, the heart, and muscle no one had identified adult stem cells in endometrium.

Background:

- Roughly 20 years ago, a biologist named Caroline Gargett went in search of some remarkable cells in tissue that had been removed during hysterectomy surgeries. The cells came from the endometrium, which lines the inside of the uterus.

- When Dr. Gargett cultured the cells in a petri dish, they looked like round clumps surrounded by a clear, pink medium.

- She strongly suspected that the cells were adult stem cells; rare, self-renewing cells, some of which can give rise to many different types of tissues. She and other researchers had long hypothesised that the endometrium contained stem cells, given its remarkable capacity to regrow itself each month.

- The tissue, which provides a site for an embryo to implant during pregnancy and is shed during menstruation, undergoes roughly 400 rounds of shedding and regrowth before a woman reaches menopause.

Several types of self-renewing cells:

- Such cells are highly valued for their potential to repair damaged tissue and treat diseases such as cancer and heart failure.

- But they exist in low numbers throughout the body, and can be tricky to obtain, requiring surgical biopsy, or extracting bone marrow with a needle.

Key observations:

- Before she could claim that the cells were truly stem cells, they measured the cells’ ability to proliferate and self-renew, and found that some of them could divide into about 100 cells within a week.

- They also showed that the cells could indeed differentiate into endometrial tissue, and identified certain tell-tale proteins that are present in other types of stem cells.

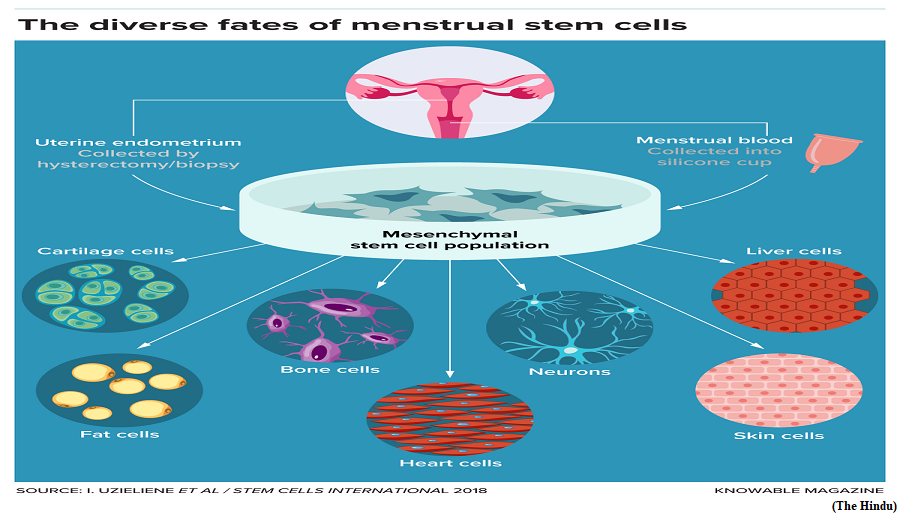

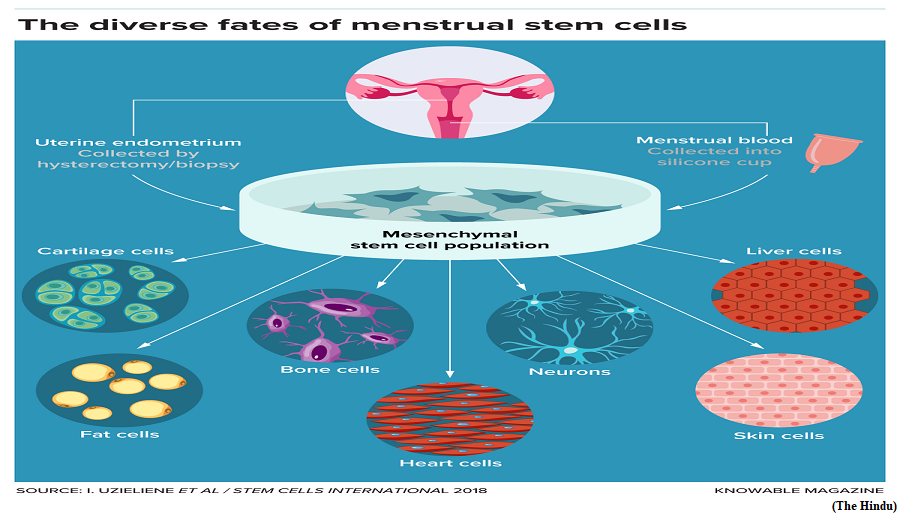

- Theywent on to characterise several types of self-renewing cells in the endometrium. But only the whiskered cells, called endometrial stromal mesenchymal stem cells, were truly “multipotent,” with the ability to be coaxed into becoming fat cells, bone cells, or even the smooth muscle cells found in organs such as the heart.

Menstrual stem cells:

- Around the same time, two independent research teams made another surprising discovery: Some endometrial stromal mesenchymal stem cells could be found in menstrual blood.

- More detailed studies of the endometrium have since helped to explain how a subset of these precious endometrial stem cells dubbed menstrual stem cells end up in menstrual blood.

- The endometrium has a deeper basal layer that remains intact, and an upper functional layer that sloughs off during menstruation. During a single menstrual cycle, the endometrium thickens as it prepares to nourish a fertilised egg, then shrinks as the upper layer sloughs away.

- Dr. Gargett’s team has shown that these special stem cells are present in both the lower and upper layers of the endometrium.

- The cells are typically wrapped around blood vessels in a crescent shape, where they are thought to help stimulate vessel formation and play a vital role in repairing and regenerating the upper layer of tissue that gets shed each month during menstruation.

- This layer is crucial to pregnancy, providing support and nourishment for a developing embryo.

- The layer, and the endometrial stem cells that prod its growth, also appears to play an important role in infertility: An embryo can’t implant if the layer doesn’t thicken enough.

Testing for endometriosis:

- Endometrial stem cells have also been linked to endometriosis, a painful condition that affects roughly 190 million women and girls worldwide.

- Although much about the condition isn’t fully understood, researchers hypothesise that one contributor is the backflow of menstrual blood into a woman’s fallopian tubes, the ducts that carry the egg from the ovaries into the uterus. This backward flow takes the blood into the pelvic cavity, a funnel-shaped space between the bones of the pelvis.

- Endometrial stem cells that get deposited in these areas may cause endometrial-like tissue to grow outside of the uterus, leading to lesions that can cause excruciating pain, scarring and, in many cases, infertility.

- Researchers are still developing a reliable, non-invasive test to diagnose endometriosis, and patients wait an average of nearly seven years before receiving a diagnosis. But studies have shown that stem cells collected from the menstrual blood of women with endometriosis have different shapes and patterns of gene expression than cells from healthy women.

Therapeutic applications:

- Menstrual stem cells may also have therapeutic applications. Some researchers working on mice, for example, have found that injecting menstrual stem cells into the rodents’ blood can repair the damaged endometrium and improve fertility.

- Other research in lab animals suggests that menstrual stem cells could have therapeutic potential beyond gynaecological diseases.

- In a couple of studies, for example, injecting menstrual stem cells into diabetic mice stimulated regeneration of insulin-producing cells and improved blood sugar levels. In another, treating injuries with stem cells or their secretions helped heal wounds in mice.

Way Forward:

- Despite the relative convenience of collecting adult multipotent stem cells from menstrual blood, research exploring and utilising the stem cells’ power still represents a tiny fraction of stem cell research.

- Through more equitable investments, menstruation will be recognised as an exciting new frontier in regenerative medicine.

The role of X chromosome in auto-immune diseases

(GS Paper 3, Science and Technology)

Why in news?

- A 2023 study by the University of Oxford stated that about 10% of the population they had studied had autoimmune diseases of which 13% were women and 7% were men.

- The higher susceptibility of women to autoimmune diseases has puzzled researchers for decades. Several factors can cause autoimmune disease such as environmental factors, genetics, hormonal imbalance and lifestyle habits.

- However, since women are more susceptible to these diseases, scientists previously thought that it could be related to sex hormones or faulty regulation of the X chromosome.

X chromosomes:

- Now, a group of scientists have found a molecular coating that is found in half of the X chromosomes in women might be the reason behind this phenomenon.

- Human females (and most mammals) contain two X chromosomes while the males of the species contain one X and one Y chromosome.

- The molecular coating of the X chromosome is a combination of RNA and proteins and is crucial to a process called X-chromosome inactivation which ensures that one set of X chromosomes in females remains active and functional in all the cells of the body while the other is muffled.

How is this achieved?

- The chromosome is wrapped in long strands of RNA called XIST that attract proteins and tamp down the expression of the gene inside.

- However, not all genes are muffled in this manner and the ones that escape the X inactivation process are thought to be the cause of autoimmune diseases.

- Not only this, the XIST molecule too has been known to elicit inflammatory immune responses.

- Many of the proteins that are attracted to the XIST also induced the response of autoantibodies, a type of antibody that reacts with self-antigens.

Key observations:

- To see if these autoantibodies attacking the XIST molecule were another reason for autoimmune diseases, they bioengineered male mice to produce a modified version of XIST which did muffle the gene expression but still retained the ability to form the RNA and proteins that covered the gene.

- They found that when a lupus-like disease was introduced in the mice, the ones that expressed XIST had higher levels of autoantibody levels than the ones that didn’t. Their immune cells were also on higher alert which suggests a proneness to autoimmune attacks.

- Since XIST is expressed only in cells with two X chromosomes, women are more susceptible to autoimmune diseases and attacks.

Way Forward:

- Further studies in this field would help in determining exactly which XIST-related antigens contribute to sex-biased immunity resulting in expedited detection and diagnosis, the authors noted.