India needs to reorient its naval strategy post Vikrant

Context:

- Recently, INS Vikrant has been commissioned into the Indian Navy by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

- Though delayed by several years, INS Vikrant is a great achievement for the Indian Navy and Indian shipbuilding.

Why India needs aircraft carriers?

- Indian Navy’s maritime doctrine draws on the lessons of India’s lack of sea control since colonial times. Although the Europeans did not launch a maritime invasion, their control of the seas had a significant impact on India’s maritime trade, before eventual colonisation.

- Sea control is the central concept around which the Indian Navy is structured and considers an aircraft carrier as a primary asset. Sea control is the ability of the navy to act freely in an area of operation. Those who control the sea deny it to the adversary by default.

- An aircraft carrier is a symbol of national power with tremendous operational capability. Depending on how they are used, it is also an excellent tool for diplomacy and political messaging to both friends and adversaries.

The vast oceans and limitations of land-based aerial assets to deliver adequate and sustained force over long distances necessitate carrier-based aviation. They can quickly move into an area of operation and operate independently for prolonged periods.

INS Vikrant in 1961:

- Developing a blue water navy centred on aircraft carriers to protect the country with vast expanses of seas surrounding it was felt soon after independence.

- The British Majestic class aircraft carrier was acquired by India and commissioned as INS Vikrant in 1961, followed by INS Viraat in 1987, both of which were decommissioned after their service lives were completed. INS Vikramadityawas commissioned in 2013.

- A rapidly growing economy, expanding interests, a large diaspora spread throughout the world, including conflict-prone regions, and the rapidly changing geopolitical and geo-economic situation, as well as responding to natural disasters in the Indo-Pacific region, have increased the Indian Navy’s responsibilities.

India as security provider:

- India relies heavily on the seas for trade and energy. As a major regional power, India aspires to be a security provider. The United States, which has been policing the oceans, is becoming increasingly stretched.

- The balance of power is shifting to the Indo-Pacific, and the rules-based order that has kept the peace since World War II is being challenged by China’s rise.

- India must not only assume a large security role in the Indian Ocean Region in order to protect its interests, but also deny the same to an adversary filling any potential vacuum.

- To back up its diplomacy, India needs naval capabilities that persuade the region’s countries to entrust maritime security to India rather than looking elsewhere.

Indian Navy’s maritime doctrine:

- The Indian Navy’s maritime doctrine focuses on the application of naval power across the spectrum of conflict, including war, less than war situations and peace.

- The maritime strategy states that in order to provide ‘freedom to use the seas’ for India’s national interests, it is necessary to ensure that the seas remain secure.

- The Indian Navy’s primary area of responsibility is the Indian Ocean Region. But with its rapidly growing economy, interests and stature, India seeks to expand its influence. The Indian Navy is deployed from the Pacific to the Atlantic. The distinction between primary and secondary areas of operation will likely get erased in the future.

China factor:

- China will contest the Indian Ocean maritime space with its growing naval might. India has interests in the South China Sea and the Western Pacific, and it deploys naval assets to the region on a regular basis, as well as participates in exercises with friendly countries.

- The two countries’ land borders are likely to remain hostile for a long time, and India will have to use naval force in the event of an all-out land war, exploiting China’s vulnerabilities in the seas to force favourable outcomes.

- Furthermore, India’s island territories of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are over 1,000 kilometres away, unfortified, and vulnerable, making carriers critical for their defence in any event.

Humanitarian assistance:

- India has been a first responder for humanitarian assistance and disaster relief as climate change and extreme weather events have become more common.

- Carriers bring not only massive force capabilities, but also relief and sealift capabilities, making them critical for India.

Why India needs a larger third carrier?

- The Indian Navy considers a third carrier an operational necessity. The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Defence recommends three aircraft carriers for navy — “to bridge operational deficiencies thus arising, three aircraft carriers are an unavoidable requirement to meet any eventualities”.

- Three carriers are required to have at least two deployed operationally while the third undergoes maintenance or refit.

- Smaller carriers, such as the INS Vikrant, carry only 20-24 fighter jets and their ski-jump design limits combat capabilities due to reduced fuel and weapon payload.

- With jets required for fleet defence, the number of aircraft available for offensive missions is reduced. A 65,000-ton carrier will be able to carry up to 40 fighter jets and full fuel and weapons loads with catapult assisted takeoff.

- This carrier will also be able to launch force multipliers such as surveillance and early warning aircraft, which cannot be launched from ski-jump carriers.

Sea control to Sea denial:

- The supposed lack of funds, and the subsequent push to prioritise submarines, appears to compel the navy to shift its doctrine from sea control to sea denial, while shifting the nation’s security outlook from maritime to land-centric.

- Sea denial is the tactic of denying an adversary access to the seas, which is primarily accomplished with submarines. Carrier battlegroups include submarines, which is why the Indian Navy refuses to view the two as binary and does not consider sea control and sea denial to be mutually exclusive.

- Vulnerability of the carrier due to detection by satellites and long range missiles has been cited, particularly the Chinese DF-21 and DF-26 ballistic missiles, dubbed carrier killer. The Chinese have yet to demonstrate operational success in hitting a ship travelling at 30 knots.

- These land-based missiles lack the range to reach the Indian Ocean, where Indian carriers will be primarily deployed. A carrier is a highly protected asset that controls vast areas of the seas and is difficult to sink. Even if a couple of missiles hit it, it will not sink.

Conclusion:

- Doctrines derived from learnings dating back to India’s colonisationcannot be discarded. It will have serious security consequences. Small countries with a brown water navy benefit from sea denial.

- Since Independence, India has envisioned a blue-water navy. At the doctrinal level, sea denial does not serve its expanding interests, counter security threats, or fulfil the aspirations as a security provider. Aircraft carriers are crucial to the Indian Navy’s ability to control the seas.

Inaugural NITI - BMZ Dialogue on Development Cooperation

(GS Paper 2, International Relation)

Why in news?

- Recently, NITI Aayog and German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) held the inaugural NITI-BMZ Dialogue of Development Cooperation via video conferencing.

The current Dialogue laid down a pathway to strengthen mutual cooperation between the two countries, particularly to reconcile the imperatives of dealing with climate change with the goals of Agenda 2030.

Background:

- On May 2, 2022, India and Germany signed a Joint Declaration of Intent on Partnership for Green and Sustainable Development (GSDP).

- During the last G7 summit in SchlossElmau in June 2022, India and the G7 had agreed to work towards a Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP).

Core areas:

The NITI-BMZ Dialogue focused on five core areas of cooperation:

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),

- Climate action,

- Energy transition,

- Emerging technologies and

- Agro-ecology.

Key Highlights:

- In support of a green and sustainable development partnership, Germany announced an additional funding of EUR 3.5 million, specifically for strengthening of implementation of SDGs and climate action at the level of Indian states.

- During the discussion, both sides highlighted the need to deepen engagement on the Lighthouse Cooperation on Agroecology and Natural Resources and to collaborate on

- scaling up natural farming in India

- strengthening research in different agro-climatic regions for natural farming practices,

- working towards standards and certification of natural farming products for facilitating export and

- evaluating impact of natural farming for mitigating climate change and adapting to climate risks.

Way Forward:

- NITI and BMZ reiterated their commitment on collaborating towards strengthening SDG localization at the city level and scaling-up SDG implementation in the context of climate change at the state level with capacity building and incentive systems for implementation.

Seat belts, head restraints and safety regulations

(GS Paper 2, Governance)

Why in news?

- The recent death of Cyrus P. Mistry, former Chairman of Tata Sons, in a car crash in Maharashtra’s Palghar district has turned the focus on whether compulsory use of seat belts in cars, including by passengers in the rear seat, can save lives during such accidents.

It is reported that Mistry and a co-passenger, who was also killed in the mishap, were not wearing seat belts. Although a full investigation has to follow, authorities said preliminary findings showed the car was moving at high speed.

How is a seat belt a life saver?

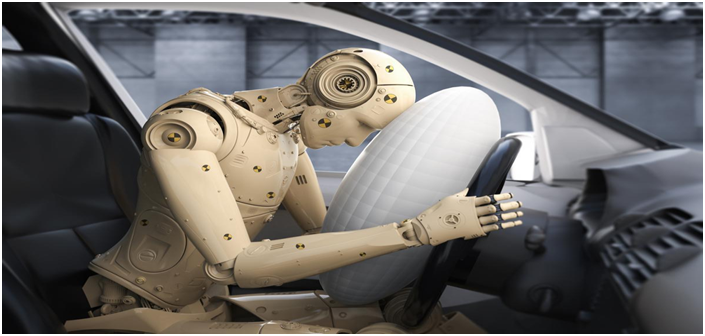

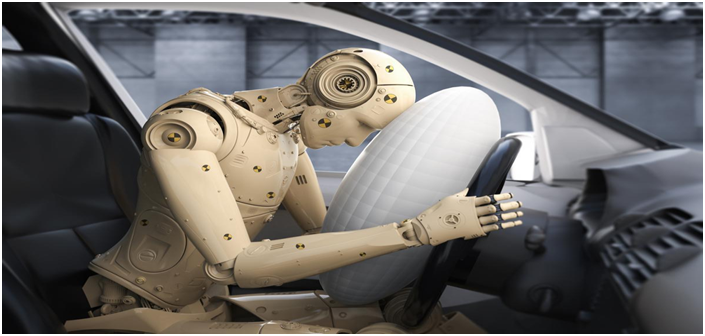

- The three-point seat belt engineered by Nils EvarBohlin, a passive safety device first incorporated into a car by Volvo in 1959, and now standard in cars sold in India, is a low cost restraint system that prevents occupants of a vehicle from being thrown forward in a crash.

- In a car crash, particularly at moderate to high speeds, the driver or passenger who has no seat belt continues to move forward at the speed of the vehicle, until some object stops the occupant. This could be the steering wheel, dashboard or windscreen for those in front, and the front seat, dashboard or windscreen for those in the rear.

- Even if the vehicle is fitted with an airbag, the force at which an unrestrained occupant strikes the airbag can cause serious injuries.

- Without an airbag, and no seat belt restraint, a severe crash leads to the occupant of the rear seat striking the seat in front with such force that “it is sufficient for the seat mountings and seat structures to fail.

Functions of seat belt:

- The seat belt performs many functions, notably slowing the occupant at the same rate as the vehicle, distributing the physical force in a crash across the stronger parts of the body such as the pelvis and chest, preventing collisions with objects within the vehicle and sudden ejection.

- Newer technologies to “pretension” the belt, sense sudden pull forces and apply only as much force as is necessary to safely hit the airbags.

- Absence of seat belts could lead to rear seat occupants colliding with internal objects in the car, or even being ejected through the front windscreen during the collision.

What role do head restraints play?

- Head restraints, which are found either as adjustable models or moulded into the seats, prevent a whiplash injury.

- This type of injury occurs mostly when the vehicle is struck from behind, leading to sudden extreme movement of the neck backwards and then forwards. It could also happen vice versa in other circumstances.

- The injury involves the muscles, vertebral discs, nerves and tendons of the neck and is manifested as neck stiffness, pain, numbness, ringing in the ears, blurred vision and sleeplessness among others.

- The head restraint built into the seat must be properly placed and aligned with the neck, to prevent the injury in a vehicle accident.

How does India regulate and enforce safety?

- On February 11, 2022, the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways issued a draft notification providing for three-point seat belts to be provided in all vehicles coming under the M1 category, that is, for carriage of passengers comprising not more than eight seats in addition to the driver's seat, for vehicles manufactured from October 1.

- Also, it stipulated relevant Indian Standards to be followed by the manufacturers for both seat belts and reminder systems alerting occupants to wear them.

- What stands out is that the amended Motor Vehicles Act of 2019 already requires the occupants of a passenger vehicle to wear a seat belt.As per Section 194(B) of the Act, whoever drives a motor vehicle without wearing a safety belt or carries passengers not wearing seat belts shall be punishable with a fine of one thousand rupees.

Non-complaince:

- Evidently, although cars are equipped with seat belts, the enforcement for rear seat occupants is virtually absent in India.

- U.S. research findings show that seat belt use was low in states with weak laws or no laws at all, and riders of taxi services are high risk groups. The study found that rear seat passengers who did not buckle up were eight times more likely to suffer serious injuries than those who did.

- The toll from non-compliance in India is high, as taxicabs often have missing seat belts.

- In one of the few questions on the subject asked in Parliament, the Road Transport Ministry said, during 2017, a shocking “26,896 people lost their lives due to non-use of seat belts and 16,876 of them were passengers. No specific data with regard to loss of lives due to non-usage of seat belts by rear seat passengers is available with the Ministry”.

Way Forward:

- In the aftermath of the accident in which Cyrus Mistry died, there have been suggestions that automotive technology should bring about compliance by making it impossible to operate the vehicle if seat belts are not fastened.

- As of July, the European Union’s General Safety Regulation requires new vehicles to incorporate advanced emergency braking technology that launches automatically when a collision is imminent, and intelligent speed assistance to reduce speed suitably besides accident event recorders, all of which are relevant to the Palghar crash.

- Making high quality dash cameras standard in cars could be a start to help record accidents and establish the cause.

Social mobility for sustainable development

(GS Paper 2, International Organisation)

Context:

- The Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) 2022 report on key indicators for Asia and the Pacific region shows that while some nations in the region are poised to bounce back, issues such as potential stagflation, cross-border conflicts, and threats to food security may prevent substantial economic progress from returning anytime soon.

- This edition of ADB’s annual exercise highlights the role of social mobility in countries, as crucial to achieving the SDGs by the end of this decade.

The Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) 2021 report on key indicators underlines the pandemic-induced impediments to the region’s ability to attain several SDGs.

Agenda 2030 and the Asia-Pacific:

- The current “Decade of Action” has gained massive relevance in the journey towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), therefore, there needs to be a galvanisation of efforts to meet the 2030 deadline.

- While the COVID-19 pandemic has crippled economies worldwide, it has also directly and indirectly impacted a host of developmental parameters ranging from poverty and unemployment to gender equality and climate change, further widening the divergences in domestic socio-economic inequalities between advanced and developing societies.

Social Mobility Index:

- Social mobility refers to the transition of people, including families and other social units, between the socio-economic strata within their lifetime. The movement of some people in and out of poverty varies across developing nations in Asia.

- For impactful transitions to occur, several upward drivers need to be improved upon which can positively impact an individual’s health, education, income, employment, and location, all of which are key factors. During the pandemic, these drivers were severely impaired, thus, denting people’s ability to experience positive social mobility in their lifetimes.

- Upward social mobility holds the essence of sustainable development because it endorses comprehensive growth and promotes social convergence in terms of access to resources, within and across nations. If developmental trajectories are not holistic and inclusive, they fail to be sustainable.

WEF’s Social Mobility Index:

- The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) created a Social Mobility Index in 2020 which ranks 82 nations and identifies areas for promoting shared opportunities in the economy.

- The index evaluates 10 pillars as apt indicators of a nation’s social mobility including health, access to education services, social protection, fair wage rates, and inclusive learning, amongst others.

- The report estimated that higher-income nations in Europe and North America tend to fare much better in terms of social mobility, thus, raising concerns for poorer countries from Latin America and the Caribbean, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa which constitute the lower end of the index rankings.

- There exists a direct linear relationship between a country’s income inequality and its social mobility scores. On one hand, nations with greater social mobility enhance access to equally shared opportunities, while on the other, higher income inequalities impede social mobility.

Social Mobility vis-à-vis sustainable development:

- Nations that have a higher degree of social mobility can have better success at reducing extreme poverty domestically.

- Firstly, the identification of sectors with high levels of poverty prevalence but low social mobility would require strong policy intervention due to the inability of persons to elevate their socio-economic status with the resources available to them.

- In such situations, it is essential to ensure that interventions are inclusive, thus, imbibing the basic tenets of sustainable development within itself.

- Secondly, upward social mobility of the lowest section does wonders for society as a whole in terms of improving resilience to exogenous shocks such as the pandemic.

- Given, that the distribution of economic prospects in ADB member economies had shrunk by about 69 percent post the pandemic, if resource equity can be established at various levels, it will invariably trickle down to further generations in the long run, with more sustainable progress.

Social mobility and the pandemic:

- Predicting how the pandemic would have affected societies had they had better social mobility is difficult to accurately determine, given the lack of data.

- However, projections certainly indicate that the nations where such mobility was low before the pandemic will end up experiencing longer periods of socio-economic setbacks.

- Despite this, developing nations in Asia are expected to bring down the occurrence of extreme and moderate poverty to 1 and 7 percent respectively by 2030. However, such outcomes will only come true if the risks associated at the intersection of economic growth and social mobility are wisely addressed.

- Prior to the pandemic, less than half the population in 72 percent of the ADB member nations were covered by social protection benefits. Though several newer cash and benefit schemes were brought in as a response to the pandemic, it is essential for such recovery measures to extend beyond a few years. Policy responses must be targeted to uplift those who were at the lowest socio-economic rungsbefore 2020 and help them achieve greater degrees of social mobility.

Way Forward:

- As mid-2022 highlights the halfway mark towards Agenda 2030, it is now also crucial to identify parameters on which high-quality, accurate and timely data must be gathered to direct resource requirements for social mobility and corresponding policy action.

- This will be extremely crucial for the Asia-Pacific, given the highest concentration of the world’s population and a large number of emerging markets in the region, which will chart the direction of the global economic order more significantly in the years to come.

Action on the developmental parameters will not only have a strong bearing on making the domestic economies and communities more resilient but also decide the dynamics of foreign investments and congenial business climate in the region.