SC marriage equality judgment unpacked, Two views on four key issues (GS Paper 2, Social Justice)

Why in news?

- A five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court headed by Chief Justice of India refused to grant legal status to same-sex marriages.

- While two judges; the CJI and Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul recognised that queer couples can form “civil unions”, they were in the minority. The majority of three judges said that the issue lay exclusively in the domain of the legislature.

The fundamental right to marry:

- The petitioners had argued that there exists a fundamental right to marry a person of one’s own choice under the Constitution, and that the court must address the denial of that right.

- If the court recognised this as a fundamental right (like it did in the case of privacy in the 2017 Aadhaar ruling), then it would cast an obligation on the state to protect this right.

Minority View:

- CJI Chandrachud did not agree with the petitioners’ argument that marriage is an inherent right that the state only regulates. The minority view stated that marriage may not have attained the social and legal significance it currently has, if the state had not regulated it through law.

- Thus, while marriage is not fundamental in itself, it may have attained significance because of the benefits which are realised through regulation.

Majority View:

- Agreeing with the CJI on this issue, the majority view differentiated between what is “fundamentally important to an individual” from an enforceable fundamental right.

- The fundamental importance of marriage remains that it is based on personal preference and confers social status. Importance of something to an individual does not per se justify considering it a fundamental right, even if that preference enjoys popular acceptance or support.

- The majority opinion also noted that the logic in many decisions by courts in the US that have underlined the rationale for declaring the right to marry a fundamental right as “being essential to the orderly pursuit of Happiness (as it appears in their Declaration of Independence) by free persons” may not be sound.

Interpretation of Special Marriage Act:

- The key framing of how the court can recognise same-sex marriage was by allowing a gender-neutral interpretation of the legislation that governs a civil marriage in which the state, rather than religion, sanctions the marriage.

- The SMA was enacted in 1954 to enable marriage between inter-faith or inter-caste couples without them giving up their religious identity or resorting to conversion.

- The petitioners had asked the SC to interpret the word marriage as between “spouses” instead of “man and woman”. Alternatively, the petitioners had asked for striking down provisions of the SMA that are gender-restrictive.

Minority View:

- On the expansive reading, CJI Chandrachud said the court could not allow that, because it would “in effect be entering into the realm of the legislature”.

- If the court were to instead grant the second option to read down the SMA to the extent that it is gender restrictive, “it would take India back to the pre-Independence era where two persons of different religions and caste were unable to celebrate love in the form of marriage.”

Majority View:

- While arriving at the same conclusion, Justice Bhat stated that the court could not interpret the SMA to include same-sex couples since the objective of the legislation is not to include same-sex couples within the realm of marriage.

- The provisions and the objects of the SMA clearly point to the circumstance that Parliament intended only one kind of couples, i.e., heterosexual couples belonging to different faiths, to be given the facility of a civil marriage.

Queer couples’ right to adopt a child

- The petitioners had argued that the guidelines of the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA), which does not allow unmarried couples to jointly adopt children, is discriminatory against queer couples who cannot legally marry.

- The guidelines allow only a couple who have been in at least two years of a stable marital relationship to be eligible to adopt.

- Individually, queer persons can adopt as single people. However, a single male is not eligible to adopt a girl child, even though a single female is eligible to adopt a child of any gender.

Minority View:

- The CJI in his opinion struck down certain CARA regulations on the grounds that the legislation’s object is not to preclude unmarried couples from adopting a child.

- The minority view added that the exclusion of same-sex couples from adopting has the effect of “reinforcing the disadvantage already faced by the queer community. Law cannot make an assumption on good and bad parenting based on the sexuality of individuals”.

Majority View:

- The majority view largely agreed with the discriminatory aspects of preventing queer couples from adopting children.

- Justice Bhat termed this as having the “most visible” discriminatory impact on queer couples, and in principle agreed that a couple “tied together in marriage are not a ‘morally superior choice’, or per se make better parents”.

- Yet, the majority view said that this change cannot be “achieved by the judicial pen”.

Civil unions for queer couples

- The halfway approach of recognising civil unions for queer couples was debated during the hearing. Before full marriage rights were recognised for same-sex couples by the US Supreme Court, several states had allowed civil unions.

- However, the petitioners argued that civil unions are not an equal alternative to the legal and social institution of marriage, and “relegating non-heterosexual relationships to civil unions would send the queer community a message that their relationships were inferior to those of heterosexual couples.

Minority View:

- The CJI located the right to form intimate associations within the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression.

- The CJI stated that for this right to have “real meaning”, the state must recognise “a bouquet of entitlements which flow from an abiding relationship of this kind”.

- The minority view noted Solicitor General Tushar Mehta’s statement that a committee chaired by the Cabinet Secretary would be constituted to set out the rights which would be available to queer couples in unions.

Majority View:

- Justice Bhat disagreed with the view that the court can prescribe a “choice” of civil unions to queer couples.

- The majority opinion said that the state should facilitate this choice for those who wish to exercise it, is an outcome that the community may agree upon.

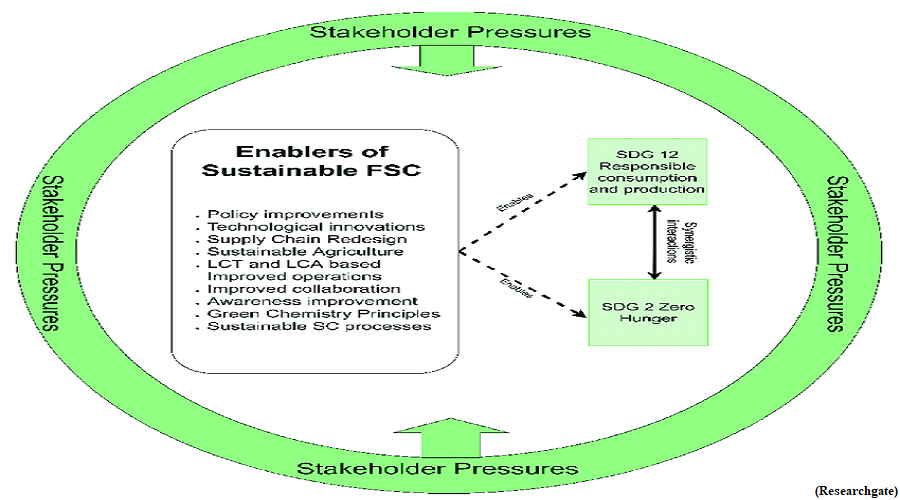

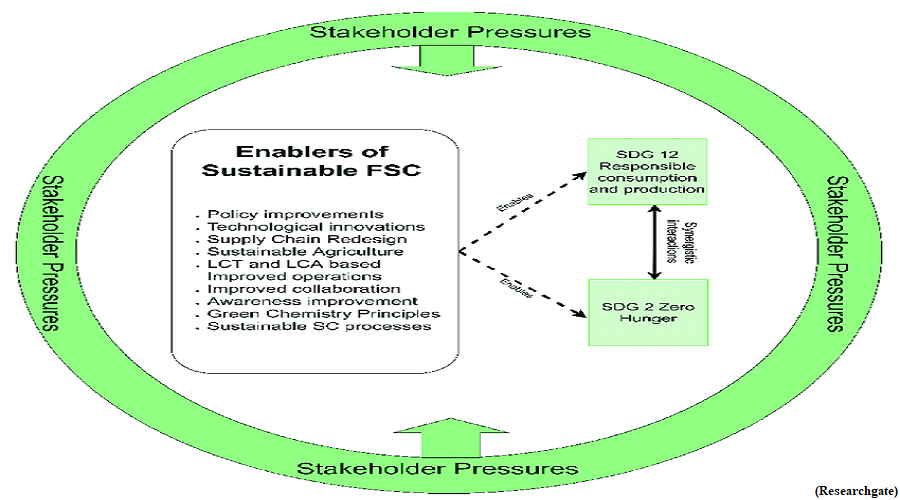

How synergistic barriers are affecting progress on SDGs

(GS Paper 3, Environment)

Why in news?

- Lamenting the lack of progress on various Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), world leaders at the SDG Summit in New York in September, once again reaffirmed their shared commitment to eradicate poverty and end hunger.

- They recognised that the world was on track to meet only 15% of its 169 targets that make up the 17 goals and have committed to an SDG stimulus of $500 billion annually.

Gaps:

- A 2023 report of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development estimated the investment gap in SDGs in developing countries to be greater than $4 trillion.

- Of this, nearly $2 trillion needs to be directed towards energy transition alone. These staggering figures, representing the estimated sum of investment required by specialised agencies responsible for tracking each SDG, seem unachievable.

Lack of synergistic action:

- A fundamental statement in the Agenda 2030 document detailing the SDGs, recognises the indivisible and integrated nature of the 17 SDGs and their contribution to the three pillars of sustainable development.

- A lot of academic literature has also focussed on the ‘synergies’ and ‘trade-offs’ that exist in the pursuit of specific SDGs.

- One such paper, identified five types of (dis)synergies that can be estimated along the value chain of an SDG intervention; those arising from resource allocations; creation of enabling environments; co-benefits; cost-effectiveness; and saturation limits.

- A recently launched UN Expert Group Report, entitled ‘Synergy Solutions for a World in Crisis: Tackling Climate and SDG Action Together’, also laments the lack of synergistic action in the face of significant (modelled) evidence.

Barrier for small-scale applications:

- The policymaking processes are generally robust, with a clear view on synergistic outcomes, especially when multi-stakeholder approaches to policymaking are practised.

- For example, in India, the push for renewable energy started with both energy security and air pollution in focus, and received an impetus with climate commitments.

- However, it hasn’t been able to leverage the health benefits arising from lower air pollution to strengthen arguments for greater incentives for renewables.

- At the same time, the ambitious renewable energy targets themselves became a barrier for small scale applications due to a misalignment of deliverables. While the energy departments had targets in gigawatts, primary health centres had needs in kilowatts, leading to their neglect in energisation, even though the health outcomes could have been significant.

- Therefore, simply recognising interlinks without a robust analysis and understanding of institutional barriers won’t yield the outcomes India desires.

Way Forward:

- As such, there is merit in both assessing as well as addressing barriers identified in the UN report in Indian context.

- This in turn should prompt the country to strengthen the environment for synergistic action, and make transparent both the opportunities and limits to synergies arising from SDG interventions.

- Every new investment today leading to a high-carbon outcome will likely result in higher dis-synergies or trade-offs in our ability to achieve our energy and climate goals.

- On the other hand, investing in clean energy options could have a significant synergistic impact on air pollution and human health, increasing the attractiveness of such interventions.

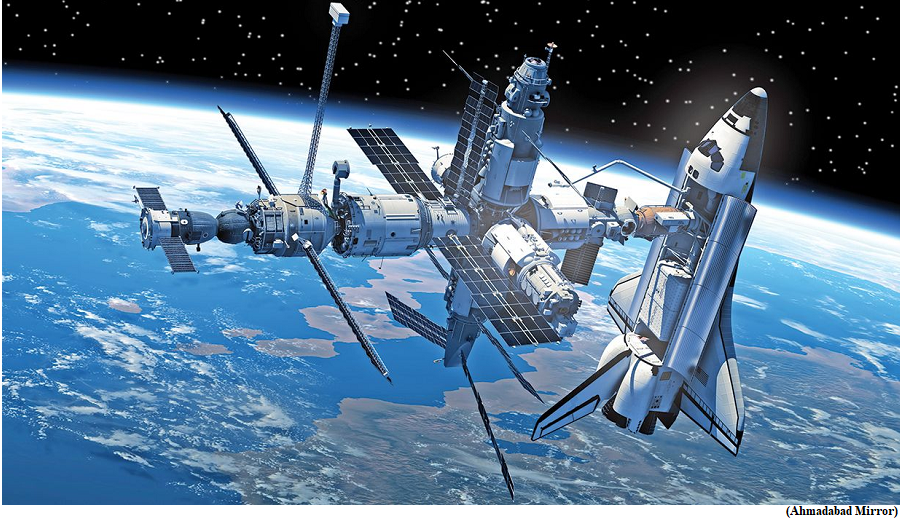

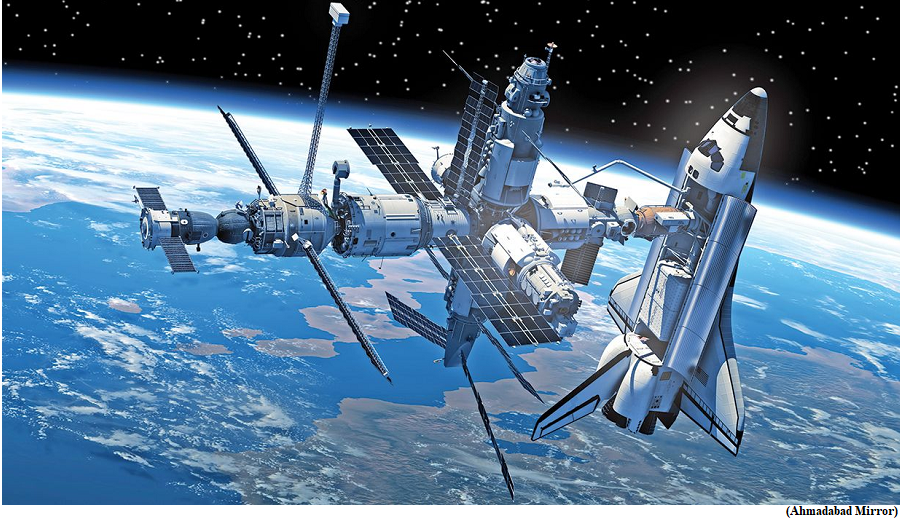

India to build Bhartiya Space Station by 2035

(GS Paper 3, Science and Technology)

Why in news?

- Prime Minister a high-level meeting recently told the Department of Space to build a Bharatiya Antariksha Station (Indian Space Station) by 2035.

- The new directive comes after India made history by successfully landing a spacecraft on the Moon and launching another to study the Sun, the two big celestial bodies that guide Earth's future.

- While India continues to grow leaps and bounds beyond the boundaries of the planet, the challenges are immense to make this 2035 target a reality.

Technology involved:

- Building a space station is a colossal undertaking that demands cutting-edge technology and expertise.

- India has shown its prowess in satellite development, but constructing and maintaining a space station requires a completely different set of skills.

- It involves life support systems, radiation protection, and long-term structural integrity. India will need to significantly upgrade its technological capabilities to meet these demands.

- With private companies stepping up, the research and technological development is set to go up and ISRO is assisting aerospace startups in the process.

Financial aspect:

- A space station is a costly endeavour, and India must secure a substantial budget. Financial constraints could potentially limit the pace of the project and the range of experiments it can accommodate.

- India will have to seek international collaborations and explore private-sector involvement to ensure adequate funding.

- There has been a constant urge from the science community to enhance the budgetary allocations to the department to push for bigger missions.

Human Spaceflight:

- While India has achieved significant success with robotic missions, it lacks experience in human spaceflight.

- To build and operate a space station, a well-trained team of astronauts is indispensable. India must invest in human spaceflight programs, astronaut training, and the development of necessary infrastructure for crewed missions.

- It will all hinge on the success and learning of the ambitious Gaganyaan Mission. ISRO is prepping for the maiden test flight of the program on October 21 from Sriharikota.

- India is targeting to launch Indian astronauts into space by 2025 onboard its indigenously developed mission.

International Cooperation:

- India's space station project should also be seen in the context of international cooperation. Collaboration with established spacefaring nations can provide valuable insights and reduce costs.

- Establishing partnerships, especially with nations possessing space station experience, can be mutually beneficial in terms of knowledge sharing and resource sharing.

- India could look towards the US, Canada, and even China to gain knowledge from their operations of the Space Station.

- While NASA, the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, European Space Agency have been operating the ISS for over two decades, China has recently joined the list with its Tiangong space station and India will have to look at these models.

Geopolitics Manuvering:

- The development of a space station has geopolitical implications. India's space station project could lead to concerns from other nations, which might view it as a strategic move.

- India will need to navigate diplomatic waters carefully to ensure that its space station ambitions do not lead to conflict or regional tensions.

Long-Term Sustainability:

- Maintaining a space station is not a one-time endeavor; it's a long-term commitment. Ensuring the sustainability of the station for decades will be a formidable challenge.

- India must develop a clear plan for regular maintenance, resupply missions, and upgrades to ensure its space station remains operational.

- It will also have to devise plans to tackle space debris and its potential impact on the environment, which is a growing concern. India needs to address these issues by adopting best practices for space debris mitigation and disposal.