Copper plates bring into focus Shilabhattarika and her poetry (GS Paper 1, Culture)

Why in news?

- Researchers recently at BORI claimed to have shed new light on Shilabhattarika; the celebrated Sanskrit poetess of ancient India by establishing her as a daughter of the famed Chalukyan emperor Pulakeshin II of Badami (in modern Karnataka).

Details:

- Pune-based Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI) houses South Asia’s largest collection of manuscripts and rare texts.

- Following the decoding of inscriptions on copper plates they said it was now reasonably certain that Shilabhattarika was a Chalukyan princess, possibly the daughter of Pulakeshin II, who ruled from 610-642 CE and had defeated Harshavardhan of Kanauj in a battle near the banks of the Narmada River in 618 CE.

Shift in historiography:

- The importance of this decipherment shed new light on Shilabhattarika, who stood out as a poetess in the male-dominated field of classical Sanskrit literature in ancient India.

- The Sanskrit poet-critic Rajashekhara, who lived in the 9th-10th century CE and was the court poet of the Gurjara-Pratiharas, had praised Shilabhattarika for her elegant and beautiful compositions.

- Noted Marathi poetess Shanta Shelke too has drawn inspiration from Shilabhattarika’s verses to compose one of her most iconic songs— toch chandrama nabhat (it is the same moon in the sky).

- The decoding of the copper plates also marks a notable shift in the historiography of Badami Chalukyas by placing Shilabhattarika as having lived in the 7th century CE rather than the current theory which has her as the wife of the 8th Century Rashtrakuta ruler Dhruva.

Copperplate Charter:

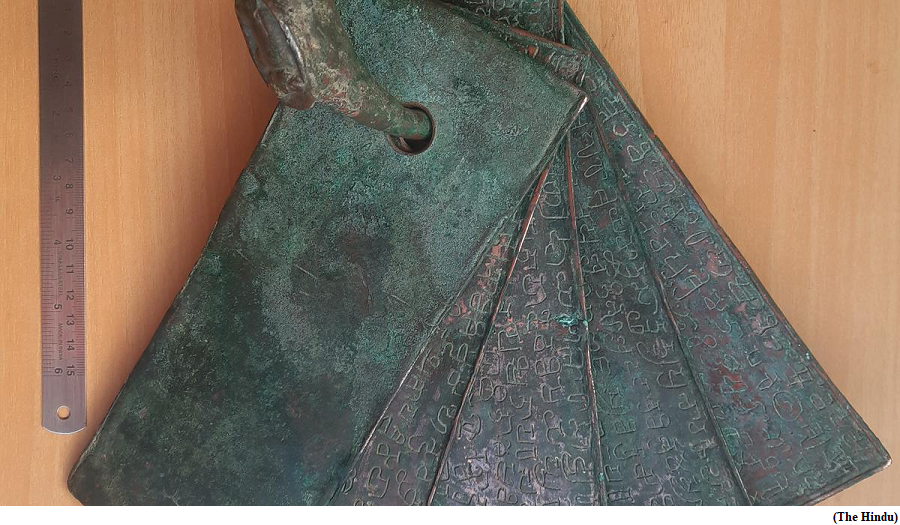

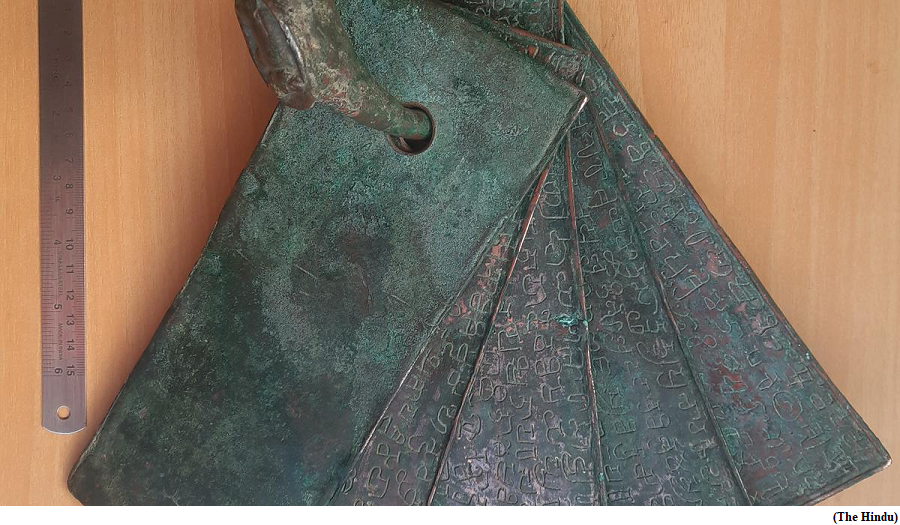

- A copperplate charter with five copper plates said to be dating from the reign of the Badami Chalukyan ruler Vijayaditya (696-733 CE) has been deciphered.

- The charter had five plates measuring 23.4 cm by 9.4 cm, held together by a copper ring bearing a beautiful varaha (boar) seal. The varaha seal is the trademark of the Badami Chalukyas.

- The charter contained a Sanskrit text with 65 lines inscribed in late-Brahmi script.

Other findings:

- A primary reading of the plates revealed that Vijayaditya had donated the village of Sikkatteru in the Kogali Vishaya to a vedic scholar named Vishnusharma in the month of Magha, Shaka year 638, corresponding to January-February 717 CE.

- The Sikkateru was identified as Chigateri situated near Kogali in the Vijayanagar district of Karnataka. But this was not all. The plates revealed that Vijayaditya had donated the village on request by Mahendravarma, the son of Shilabhattarika.

- The (decoded) text goes on to say that “on recommendation of Mahendravarma, King Vijayaditya Chalukya had donated the village of Chigateri to a scholar Vishnusharma.”

Significance:

- More than genealogies, the decipherment brings into focus the importance of Shilabhattarika and her poetry.

100 episodes of PM Modi’s Mann ki Baat: Understanding the power of radio

(GS Paper 2, Governance)

Why in news?

- Recently, ‘Mann Ki Baat’, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s popular radio programme, completed 100 episodes.

- Over the last almost nine years, the broadcast experiment that had a global history but no significant Indian precedents, has become a successful element in the communications strategy of the Prime Minister, a leader who believes in talking directly to the masses.

In terms of similar global examples of radio broadcasts, what came before Mann ki Baat?

Franklin D Roosevelt:

- The earliest example of the use of radio broadcasts by a national leader remains the “Fireside Chats”, a series of 30 radio addresses, each typically 20-30 minutes long, delivered by United States President Franklin D Roosevelt between 1933 and 1944.

- The chats were popular, and played a role in shaping American public opinion on a range of issues at a time when the US battled with crises ranging from the Great Depression to World War II.

- He also used the chats to counter criticisms from the conservative media and to unpack his policies to the American public without the use of intermediaries.

Ronald Reagan:

- Decades later, Ronald Reagan used a daily radio commentary that ran from 1975 to 1979 to build a reputation as a “great communicator”, and to prepare the ground for his successful presidential run in 1980.

- He gave 1,027 addresses, reaching an estimated audience of 20-30 million listeners every week.

- The radio commentaries helped Reagan transition from a national public figure appreciated more for his acting ability than his political acumen into a serious political figure.

S.C. Bose:

- Earlier, in an entirely different context, Subhas Chandra Bose had started Azad Hind Radio as part of Germany’s radio service, first broadcasting on January 7, 1942.

- The programmes were meant to create bonds between Indians living abroad with those in the motherland under British colonial rule.

What are the issues/ themes that the PM has referred to most frequently?

- Yoga, women-led initiatives, youth, and cleanliness have been among the most touched-upon topics on Mann ki Baat since it began in October 2014.

- The PM has also frequently spoken of the valour and sacrifice of India’s soldiers, the nation’s cultural heritage, and recounted the stories of the life and work of Padma awardees and other achievers. He has also spoken on issues of science and environment.

- The PM has dwelt on khadi at length, transcripts of episodes show. He had casually asked people to wear khadi during the first episode of the programme.

Has Mann ki Baat been a political/ electioneering tool of the PM?

- One of the salient features of the programme is its non-partisan approach to social issues. It has helped to widen and deepen its reach, and allowed the PM to convey his ideas to a broad spectrum of people.

- During the two years of the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns, almost all episodes had a health-related capsule.

- The PM repeatedly underlined the need for socially responsible and Covid-appropriate behaviour, and widespread vaccinations as the country battled the coronavirus.

- The PM has also used the platform extensively to spread awareness about government schemes and initiatives; exports, the e-marketplace initiative, Pradhan Mantri Sangrahalaya, Azaadi ka Amrit Mahotsav, Har Ghar Tiranga, digital payments, startups and unicorns, and advancements in the space sector.

What are the chords that Mann ki Baat strikes with listeners?

- Mann ki Baat is consciously not a monologue by the PM. The design of the programme is participative, and involves the engagement of citizens.

- A backend communications network involving people writing in, and the PM personally engaging with ordinary people on the show, has increased interest.

- Almost every show includes some new and interesting little-known information about India’s arts, craft, folk culture and heroes, etc. that inform and educate, and evoke and sustain listener interest.

The Subaltern School and Guha’s contributions to South Asian Studies

(GS Paper 1, Modern India)

Why in news?

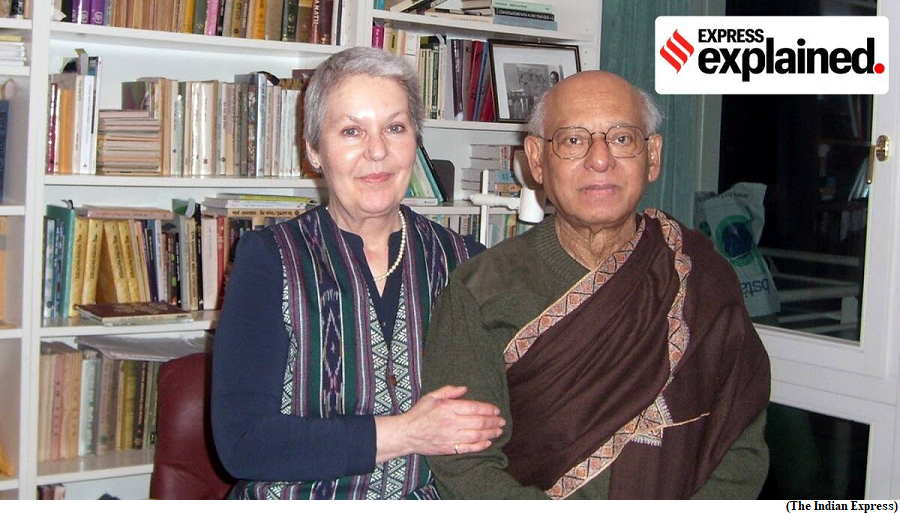

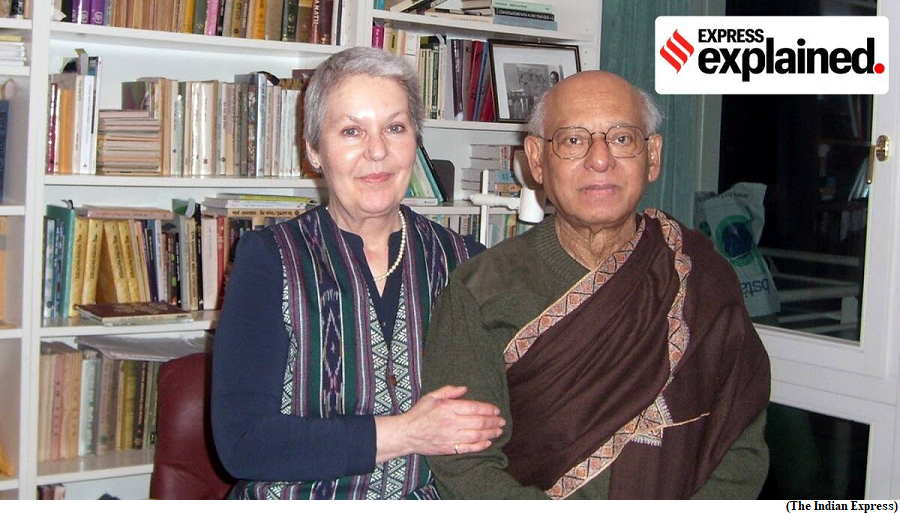

- Recently, Historian Ranajit Guha passed away.

- He ushered in a new way of studying South Asia, departing from the primacy of elitist concerns that had previously dominated scholarship.

Subaltern School:

- He, alongside his collaborators (many of whom were his students), began the Subaltern School, which remains one of the most influential post-colonial, post-Marxist schools in history.

- Over time, the influence of this school has transcended South Asian history to shape scholarship from across the world and on various facets of life and society.

Details:

- Born in Siddhakati, Backerganj (present-day Bangladesh) on May 23, 1923, he migrated to the UK in 1959. There he was a reader in history at the University of Sussex.

- While studying and teaching Indian history, he recognised that mainstream historical narratives in and about India were grossly inadequate to study the complexity of India’s past. Crucially, what traditional narratives missed was the voice of underclasses – the subaltern.

Term ‘subaltern’:

- The term “subaltern” was first coined by Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci to refer to any class of people (for Gramsci, peasants and workers) subject to the hegemony of another, more powerful class.

- This term was picked up by Ranajit Guha and like-minded colleagues in the early 1980s in their attempt to “rectify the elitist bias characteristic of much of research and academic work” in the field of South Asian studies.

Context of the Subaltern School:

- Mainstream scholarship on South Asia, prior to the Subaltern School, was either a product of colonial Eurocentrism or dominated by concerns of native elites, often heavily influenced by colonial frameworks and narratives themselves.

- For instance, James Mills’ three-part classification of Indian history into ancient (Hindu), medieval (Muslim) and modern (colonial and post-colonial) remains influential till date, having shaped generations of nationalist historians.

- However, not only is this an unthoughtful imposition of a prevalent framework used to study European history, this also misses out a diversity of experiences that should feature in historical study.

- Even left-wing academics who ostensibly were writing about the masses were unable to completely shed European frameworks and Marxist orthodoxy which privileged class as the overarching category of historical analysis.

- They were oblivious or dismissive of specific Indian modes of subalternity and hence were unable to truly appreciate Indian society in its complex richness and nuance. The Subaltern School came and changed this.

Peasant consciousness:

- In his enduring classic, Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India (1983), he writes about peasant consciousness and different modes of expression of dissent by peasants in colonial India.

- While peasant resistance had been documented since the beginning of colonial rule. His approach was fundamentally different. His work focussed on studying peasant insurgency from the perspective of the peasant. It provides insurgent peasants their own political agency rather than one supplied to them by native elites.

- Methodologically, even when he looks at commonly used historical sources such as colonial documents, his approach problematizes them, aware of the positionality of the creators and consequently, aware of possible biases in the sources themselves.

Some criticisms of the Subaltern School:

- While the Subaltern School has been extremely influential in guiding generations of scholarly work on South Asia and post colonial societies since the 1980s, it has not been without its critics.

- One of the main criticisms of the Subaltern School is its focus on agency at the expense of structure. Critics argue that the Subaltern School tends to overlook the ways in which social and political structures constrain the agency of subaltern groups. As a result, the Subaltern School has been accused of presenting an overly romanticised view of subaltern agency and resistance.

- Furthermore, the Subaltern School’s approach to politics tends to be overly focused on identity-based movements and resistance.

- This approach overlooks the importance of class-based politics and the potential for subaltern groups to engage in transformative struggles that challenge the existing economic and political structures. This is especially true of more recent work from the School.

- Lastly, in a bid to problematize the Eurocentrism of traditional Marxists, the Subaltern School, has taken a turn in the opposite extreme, rejecting any form of universal theorising as incapable of explaining particularities of South Asia.